Ever since I have been on-staff at a tertiary care academic hospital, I have made it a point to teach all the students and residents I work with about the ‘laryngospasm notch’. Specifically, since it is my standard care for every patient I extubate, I make sure trainees are applying firm pressure in the laryngospasm notch after they extubate every patient. Usually, the first residents have ever heard of the ‘notch’ is from me! This is disappointing since this manoeuvre is extremely important in clinical anesthesia, and every anesthesia practitioner should know about it. I therefore thought I would write a blog post about it.

What is the laryngospasm notch, and why haven’t you heard of it before?

I’ll get to the first question in a bit. The answer to the second question is I have no idea, because this technique is so super-important I am amazed everyone doesn’t already know about it! As its name implies, the notch is used to treat (and prevent) laryngospasm. Before we get into the details about the ‘notch’, though, let’s first consider what post-extubation laryngospasm is and why it’s important.

Post-extubation laryngospasm

Once in a while, due to secretions sitting on the vocal cords, stimulation of the vocal cords as the tracheal tube is being removed, mid-plane depth of anesthesia, or other reasons, a patient’s vocal cords will seize shut after the tracheal tube is removed at the end of an anesthetic. This means no gas can enter or leave the lungs despite the fact that the patient may be making respiratory efforts! Becuase it is difficult to predict which patients may develop this serious complication, until you can verify the movement of gas in and out of the patient’s mouth and/or nose after extubation of the trachea, you should assume the patient has laryngospasm. To do otherwise is foolhardy and potentially risky for the patient.

I have witnessed many occasions where someone has extubated the patient and held a mask over the patient’s face, but without seeing the bag on the anesthetic machine move. These patients might have been breathing (i.e. the respiratory muscles were being activated by the brain), but they were not ventilating (i.e. no gas was moving in and out of their lungs because the patient was breathing against a closed glottis).

Post-extubation laryngospasm is a serious problem, becasuse unless it is treated successfully, it is quickly followed by “bad things”, including:

- hypoxemia

- hypercarbia / respiratory acidosis, and eventually,

- negative pressure pulmonary edema (since, as the patient is still breathing and generating negative intrathoracic pressure, fluid can literally be “sucked” out of the intravascular fluid into the alveoli).

Negative pressure pulmonary edema can occur surprisingly quickly. In a young healthy patient breathing actively against a closed glottis, it can develop within a few breaths.

So, after tracheal extubation, it makes a lot of sense to be proactive in ensuring the patient actually has a patent airway before you relax after extubating someone.

Typical treatment of laryngospasm

Over the years, many potential treatments for laryngospasm have emerged, including:

- trying to “break” it with positive pressure mask ventilation and 100% oxygen

- aggressive chin-lift/jaw thrust

- applying CPAP via a face mask

- low- or high-dose succinylcholine (IV or IM)

- propofol bolus

The problem with all of the above techniques is that they have variable success rates. Additionally, in the case of succinylcholine or propofol, one must ensure the drug is drawn-up and ready to use. In contrast to the above techniques, applying pressure in the laryngospasm notch treats laryngospasm with almost complete success and can be applied in all patients immediately.

So, where is this awesome laryngospasm notch?

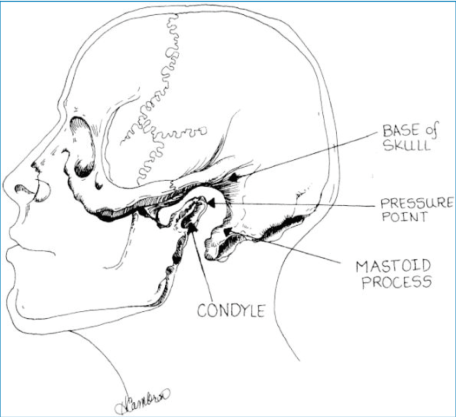

It is easiest to describe where the notch is by landmarking on yourself. So, just behind your earlobe, point your middle (or index) finger towards your skull base and place the tip of your finger on the mastoid process. Next, bring your finger anteriorly until you feel the ascending ramus of the mandible (you may need to bring your finger down — caudad — a little bit). In between the mastoid and the ascending ramus of the mandible, when you apply cephalad pressure, you will feel a ‘notch’. This is the laryngospasm notch. See the drawing below for a nice graphical representation of the notch. (This Figure is from a seminal paper by Larson, published in Anesthesiology — Larson CP. Laryngospasm–the best treatment. Anesthesiology 1998; 89(5): 1293-94.)

The Technique

The technique is very simple: apply firm cephalad and medial pressure in the laryngospasm notch (either one side or both sides). That’s it! This manoeuvre will almost always break laryngospasm without any drugs, and it will do it very quickly in the majority of cases. An additional benefit is that, even if the patient does not have laryngospasm, applying pressure in the notch will:

- prevent laryngospasm from occurring

- increase the respiratory rate

- increase tidal volume at a time when many patients need a bit of stimulation.

NB: You should be aware that applying pressure to the laryngospasm notch is quite distinct from the typical grasp an anesthesiologist uses to hold a mask on a patient, which is at the angle of the mandible and the chin. The laryngospasm notch is quite a bit further cephalad, and the ‘mask grasp’ is inadequate to break most cases of laryngospasm. See the photo below where the left hand holds the mask in the usual fashion whilst the right hand applies pressure in the laryngospasm notch.

The History of “the Notch’

As far as I’m aware, nobody has claimed the ‘discovery’ of the notch. However, the first time it received significant attention in an anesthesia journal was in 1988 in Anesthesiology when an Emeritus Professor of Anesthesia at Stanford, Philip Larson, wrote an article entitled ‘Laryngospasm–the best treatment.‘ In this article, he described the conventional means of treating laryngospasm, what the laryngospasm notch was, and how it should be properly stimulated. The fact that this paper was published so long ago and that all anesthesia practitioners don’t already know about it is, quite frankly, incredible to me.

Summary and Recommendations

When you extubate your next patient, and all patients who follow, make a point to press firmly on the laryngospasm notch, at least with one hand. I do it by pressing with my right middle finger as I am concurrently applying a mask with high-flow oxygen with my left hand (in the usual ‘mask grasp’ fashion). Applying the pressure prevents and/or treats laryngospasm post-extubation, and it also stimulates ventilation, which makes it easier for me to assess whether or not the patient has a patent airway.

The only contraindication to pressing on the laryngospasm notch is if you might be able to harm a patient by doing so. In patients who have just had neurosurgery or a mastoidectomy, I ensure I press on the non-operative side.

Any pain felt by the patient will not be remembered, as you are only pressing in the most early stages of emergence from anesthesia. Bluntly, the gain is a lot more than the pain. I encourage everyone to adopt this practice. As always, I encourage your feedback, either in the comments below, or via Twitter.

Here’s to eliminating post-extubation laryngospasm!

Addendum: I was alerted to a video showing the Larson manoeuvre. Thanks to @TheButterdog !

Reblogged this on gasdoc2857 and commented:

Nice tip. Now to get a patient with laryngospasm

LikeLiked by 1 person

This may seem like a strange question, but do you think a person could apply this maneuver to themselves to relieve a Laryngospasm? I randomly experience Laryngospasms just out of the blue that are terrifying, especially because they seem to last longer each time I have one. Last time it happened I nearly passed out before the vocal cords finally relaxed enough for me to breathe. I am a Nurse Practitioner and I know exactly what’s happening so I try to just stay calm but it’s hard when you have no airway. I guess I’ll let you know next time it happens.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t know the answer to your question, but please do let me know if it works for you. I am curious!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a GOOD question. In fact, a lady contacted me (I’m a retired nurse, and had laryngospasms starting in the year 2000), just the other day (March, 2016), due to my website (“Can’t Breathe? Suspect Vocal Cord Dysfunction!”). And she wants to learn how to do the “Larson maneuver” to stop her infrequent laryngospasms, that close (adduct) her vocal cords totally (no air coming in or out)!

The Larson method (laryngospasm notch pressure method –including forward jaw thrust), might also help those whose vocal cords aren’t fully closed during a laryngospasm, but who haven’t found any FAST-ENOUGH way to open up those spasming vocal cords!.

I added some info on webpage 4, about the Larson maneuver, but would like to refine what I wrote. Anybody here know Dr. Larson? Call my cell: 970-531-5000

Carol (http://cantbreathesuspectvcd.com is link to home page).

LikeLiked by 3 people

I too have had this problem. The trick is to breath like you are sucking air through a small straw. Some even practice that. It has worked for me ever since. Somehow changes the shape of your posterior pharynx? Actually saw a video on you-tube

LikeLiked by 2 people

This just happened to me. Very scary. I remember it happening years ago. But this one was brutal. Even afterwards for a good half hour I’ve been trying to relax and clear my throat which seems to be sort of an acid reflux. After searching the Internet I came across this article and applied the pressure to what I believe to be the notch and I actually feel like it helped relieve the slight constriction that was still present. Thank you statsdoc for posting this great information..and thanks Tina for your input

LikeLike

Great article you wrote, lauding Dr. Larson! Following up:

I would like doctors (anesthesiologists and GP/General Practitioners, etc.), Speech Pathologists, and others, to TRY using the Larson Maneuver/Technique on AWAKE patients who are having a laryngospasm/VCD/Vocal Cord Dysfunction attack, and I would like doctors, speech pathologists and others, to TEACH the Larson Maneuver to those awake laryngospasm/Vocal Cord Dysfunction patients.

Let me know the results of how the Larson Maneuver/Technique works on fully awake patients (not just patients coming out of anesthesia)!

And “rambling” Doctor____________, in Canada, please contact me about such an “informal” clinical trial for laryngospasm patients who are AWAKE, when they have a laryngospasm (also known as a VCD/Vocal Cord Dysfunction) attack.

Sincerely, Carol Sidofsky

website: “Can’t Breathe? Suspect Vocal Cord Dysfunction!”

http://cantbreathesuspectvcd.com (link to home page)

cell phone: 970-531-5000

email: fsds@rkymtnhi.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m having to go under general anesthesia in a few days. About 12 years ago I suffered laryngospasm after surgery, and was terrified. I didn’t have another episode until sometime this year, and have had these non-anesthesia related episodes about 4 times this year. Needless to say, I’m terrified about my upcoming surgery. My doctor knows what I have (actually, he just informed me what it is called the other day), but am unsure if he or the anesthesiologist have ever dealt with a patient who this has happened to. Any recommendations as to how to bring this up with them so they won’t get offended? I’m to the point that I may be cancelling my surgery due to fear of one of these attacks after the tube is removed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this. I am a Biologist so no clinical experience. I suffer from horrible laryngospasms multiple times every night due to GERD. My regime upon waking in breathing slowly, try stay calm and manage the cough, manage the acid and try breathe vapours from hot water.

I tried applying pressure with my latest attack and it really helped. I did it a bit gradually

How strong a pressure is to be applied exactly? Like squeezing a lemon to make a lemonade or more of a gentle, constant, gradual pressure?

LikeLiked by 2 people

My waking laryngospasms also follow reflux and they can be terrifying. Controlled breathing helps but it’s not enough. Last time, I felt the onset of hypoxia and suspect I was seconds away from blackout when the air started moving again. I’ve since started with omeprazole, which stopped the laryngospasms. Thanks for this post. I shall try it next time it happens to me. Jaw forwards. Squeeze the pressure points both sides and push up. Got it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To follow up my comment from Dec 2017, it’s now Feb 2022, and I’ve not had another episode. I took omeprazole for six months after diagnosis and have taken Gaviscon Advance ever since. I’ve been limiting my food intake after 7.30pm to only water or one glass of milk. In that time, there have been only two occasions where I’ve felt the onset of a laryngospasm, and both times I managed to control it, thankfully before getting to the stage of needing to use this technique. On the two occasions I mention, the following prevented it getting more serious:

– remaining calm

– remaining upright, with a very erect posture, shoulders back

– spitting out anything in my mouth

– not swallowing until the feeling subsides

– once the feeling has subsided, drinking a glass of water

– afterwards 10-15 mL of Gaviscon Advance just in case.

It’s hard to say but I think simply knowing the cause and understanding the anatomy and physiology involved has been an important part of learning to prevent the laryngospasms. Whether six months of omeprazole helped I really don’t know. I definitely still have reflux, which tends to happen in my sleep. And I still have the technique recommended here in my back pocket if the list above doesn’t arrest the developing episode.

LikeLiked by 1 person

it works on awake people, i do it to myself and it works in about 5-10s of holding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I;ve had this problem for 50 years, just discovered solution (larson maneuver) not looking forward to trying it, learnt to manage it, by not panicking firstly,stop the intake of breathe through the mouth, breathing control as above, the last one this week completely drained me. I hope doctors take note of the above comments. it truly is frightening especially for first timers…

LikeLiked by 1 person